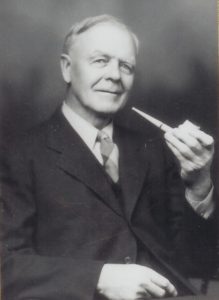

Notes on William Garner Sutherland

Generally, William Garner Sutherland is regarded as the father of cranial osteopathy. Most of today’s craniosacral approaches are built on his work. Other noted osteopaths and chiropractors at that time also explored craniosacral approaches. These include names widely recognized in the field today. Cottam, DeJarnette, and Weaver are among them. However, Sutherland is largely regarded as the first to develop the work and teach it systematically.

I read a lot of cranial text. I listen to people lecture, and, well, the stories vary. Opposing doctrines have developed from his work.

Let’s explore his story…

Sutherland was an ambitious person. He left home at an early age and worked for a newspaper. He had a brother who benefited from osteopathic treatment. Somewhere along the way, he decided to go to osteopathic school and became a Doctor of Osteopathy in 1900.

Early Direction and Challenges

It is recognized that Sutherland was fascinated with cranial bones at the School of Osteopathy in Kirkwood. He describes them in his writing as “like the gills of a fish.” Further, they resemble a “primary respiratory mechanism.” Continuing, his writing states that the structure of cranial bones indicates mobility.

Another osteopath, Charlotte Weaver, was employed by Andrew Taylor Still to establish osteopathic principles for the school’s osteopathic text. At the time, arguments existed about Sutherland’s theory on the primary respiratory mechanism, and it was excluded from Weaver’s early work.

In an effort to dismiss ideas about cranial motion, Sutherland became obsessed with palpating his head and the heads of others. His first wife referred to this as his “bony phase.” He carried bones with him everywhere, and they were all over their house. This obsession became a strain on the marriage and eventually led to their divorce.

Nonetheless, Sutherland established that a separate motion from breathing and heart rate exists. He constructed helmets for himself that could apply pressure to certain parts of his head. His second wife, Adah, and others recorded observations about his posture, pain, and even personality changes. He developed more “helmets” from leather straps and different objects to experiment with changing his cranium. There is a common story about Adah releasing him from the helmet, which rendered him helpless. As he recovered, he observed fluid movement in the spine and sacrum. This led to greater interest in the connection between the cranium and sacrum.

Controversial Publications

In the fall of 1929, Sutherland mentioned his hobby at the Minnesota State Osteopathic Association meeting. Afterward, he wrote articles on the topic under the pen name “Blunt Bone Bill.” In 1932, he presented his approach again at a meeting. And, in 1939, despite strong opposition to the cranial concept, he presents his book, The Cranial Bowl. It was widely read and quite controversial. And, in 1940, his invitation to speak on The Cranial Bowl was withdrawn because of protest.

In the early 40s, Sutherland’s work gained interest in some groups. By 1943, A Manual of Cranial Technique is published. The authors, Rebecca and Howard Lippincott, are doctors of osteopathy and followers of Sutherland’s concept. Afterward, Sutherland began teaching regular post-graduate classes starting in 1944. In 1945, with the Lippincotts, he published studies on infantile cranial osteopathy.

In 1946, the Osteopathic Cranial Association was founded as a branch of the Academy of Applied Osteopathy. Sutherland’s work gained greater acceptance, and he received numerous honors through the late 1940s. By late 1951, Osteopathy in the Cranial Field is published by Harold Ives Magoun. Based on sales figures of the time, it is well-received.

In 1953, The Sutherland Cranial Teaching Foundation was established.

Sutherland’s definition of the biomechanical model of the craniosacral system was groundbreaking. He was a tireless researcher and had an insatiable curiosity for defining the anatomical and physiological aspects of the craniosacral system. Osteopathy in the Cranial Field has details that would seem difficult to render in a time of such limited technology. Yet, Sutherland proved his idea of a craniosacral system with a primary respiratory mechanism that inhaled and exhaled cerebrospinal fluid. This research created a solid following among approaches that focus on biomechanics such as Cranial Osteopathy.

This picture is adapted from the 1951 book Osteopathy in the Cranial Field. It shows how the SBS mechanism moves during extension. This biomechanical osteopathic model was defined in detail under his teaching foundation. Each section of each bone is detailed in its structural anatomy and physiology through the craniosacral cycle. This book also included assessment and treatment techniques.

By the time this book was published, Sutherland was moving on to an approach that would become the biodynamic model. 2nd and 3rd editions of this book are edited to exclude those concepts.

Birth of Biodynamic Craniosacral

In the late 40s, Sutherland had an experience while tending to a dying man. Unexpectedly, he noticed a different, longer cycle. He referred to it as the “Breath of Life.” He believed it to be the expression of “Intelligence” with a capital “I.” He shifted his focus to observe the cycle as it passed through structures rather than manipulating those structures. He began to diagnose and treat with “The Tide.” Again, his paradigm shift strongly split the practitioners’ field. This split created a different craniosacral approach, Biodynamic Craniosacral, which integrates both his scientific research and spiritual views.

Like Palmer, the founder of Chiropractic, and Still, the founder of Osteopathy, Sutherland regarded the life force as part of the healing process. The language around these ideas began to straddle the concepts of science and spirituality. On the one hand, biomechanical practitioners remove restrictions, lesions, and obstructions to maintain homeostasis. On the other hand, biodynamic practitioners recognize spiritual life as the source of healing.

“Within that cerebrospinal fluid, there is an invisible element that I refer to as the ‘Breath of Life.’ I want you to visualize this Breath of Life as a fluid within this fluid, something that does not mix, something that has potency as the thing that makes it move. Is it necessary to know what makes the fluid move? Visualize a potency, an intelligent potency, that is more intelligent than your own human mentality.” – W. G. Sutherland DO

Sutherland died in September of 1954. He was a true visionary with the humility, will, and persistence to struggle for his cause. This led to wide-spread acceptance in his field during his 70s. He left a legacy that has inspired ongoing research and study in a field that continues to grow.

Support Integrative Works to

stay independent

and produce great content.

You can subscribe to our community on Patreon. You will get links to free content and access to exclusive content not seen on this site. In addition, we will be posting anatomy illustrations, treatment notes, and sections from our manuals not found on this site. Thank you so much for being so supportive.

Cranio Cradle Cup

This mug has classic, colorful illustrations of the craniosacral system and vault hold #3. It makes a great gift and conversation piece.

Tony Preston has a practice in Atlanta, Georgia, where he sees clients. He has written materials and instructed classes since the mid-90s. This includes anatomy, trigger points, cranial, and neuromuscular.

Question? Comment? Typo?

integrativeworks@gmail.com

Follow us on Instagram

*This site is undergoing significant changes. We are reformatting and expanding the posts to make them easier to read. The result will also be more accessible and include more patterns with better self-care. Meanwhile, there may be formatting, content presentation, and readability inconsistencies. Until we get older posts updated, please excuse our mess.